RACI Tells You Who Does the Work. It Doesn't Tell You Who Drives It.

A practical guide to RACI, RASCI, DACI, RAPID, and MOCHA – and which one actually works for transformations

At a glance (30 seconds)

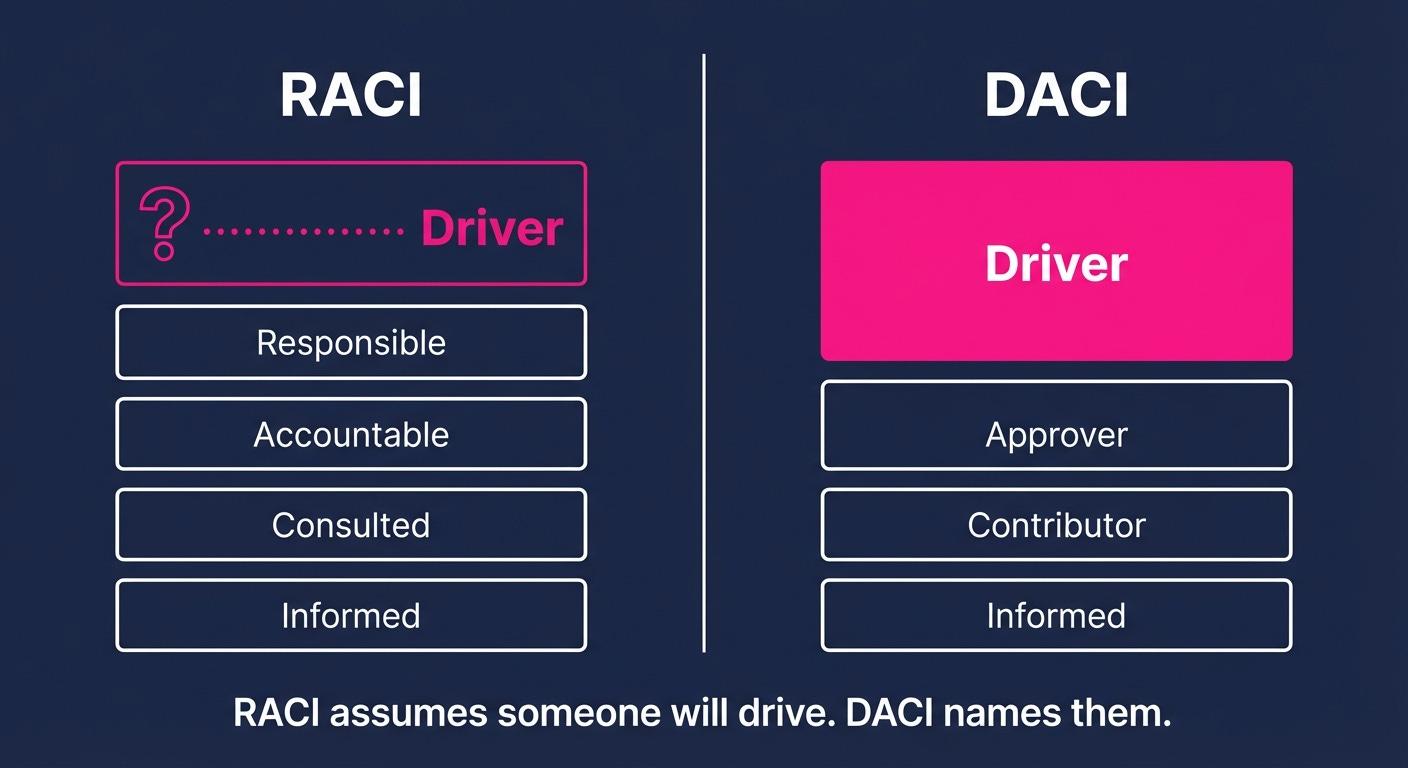

RACI defines who does the work (Responsible) and who signs off (Accountable), but not who drives it forward

In multi-partner programmes, this gap creates decision paralysis, accountability games, and finger-pointing

Five governance frameworks exist: RACI, RASCI, DACI, RAPID, and MOCHA – each designed for different contexts

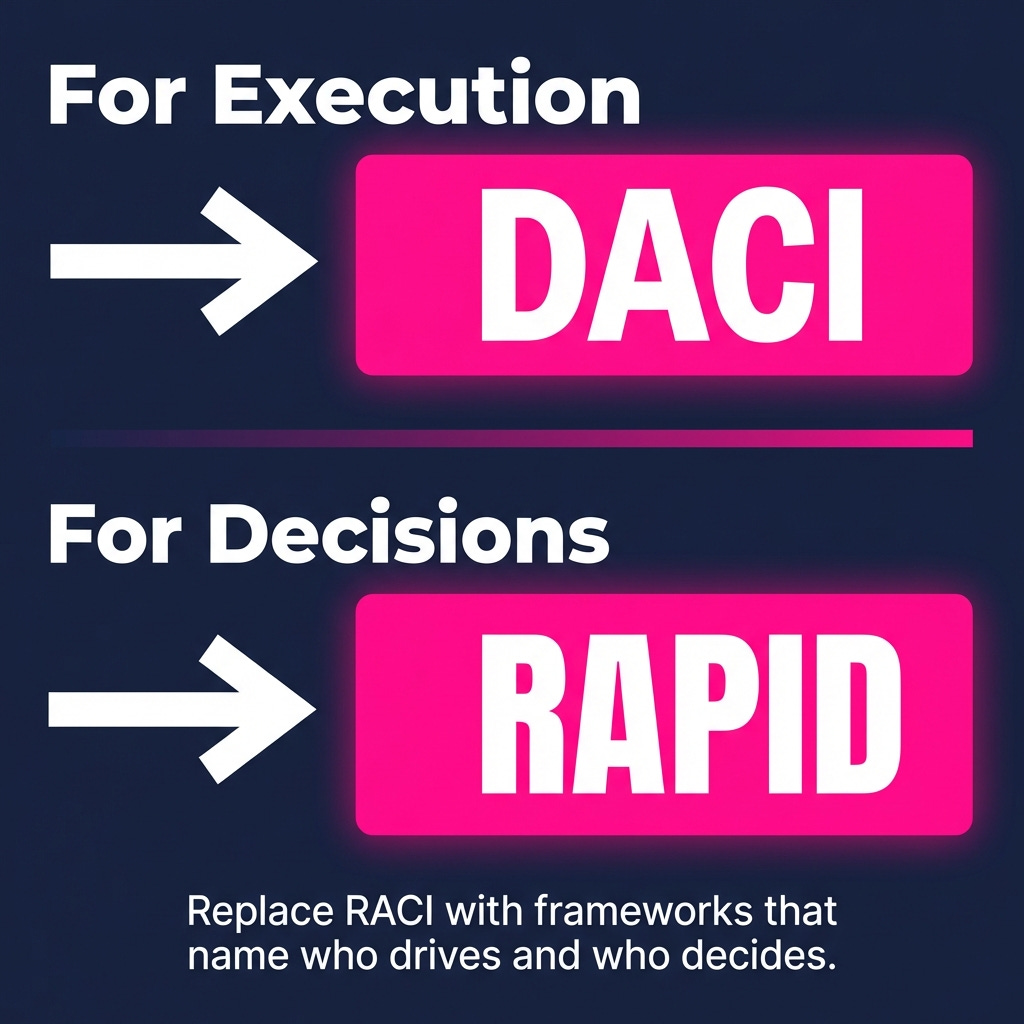

For transformation execution, DACI is the right choice: it explicitly names the Driver (who ensures work moves forward) and the Approver (who makes the call)

For steering committee decisions with multiple stakeholders, add RAPID to name a single Decider

This article reviews all programme governance frameworks and explains why DACI wins for transformation programmes

You are in a steering committee. The RACI chart is on the screen. The vendor is Responsible for data migration. The client sponsor is Accountable.

Someone asks: “Who is making sure this actually happens? Who is engaging the right stakeholders, scheduling the workshops, chasing the decisions?”

Silence.

The vendor says: “We are doing the work, but we cannot force client decisions.”

The sponsor says: “I am accountable for the outcome, but I am not running this day-to-day.”

Everyone has a letter. No one is driving.

This is the governance gap that quietly kills transformation programmes. Not missing processes. Not bad intentions. Just a framework that assumes someone will drive without ever naming who.

Sound familiar?

Before we go further, I’m curious what you’re seeing in the field.

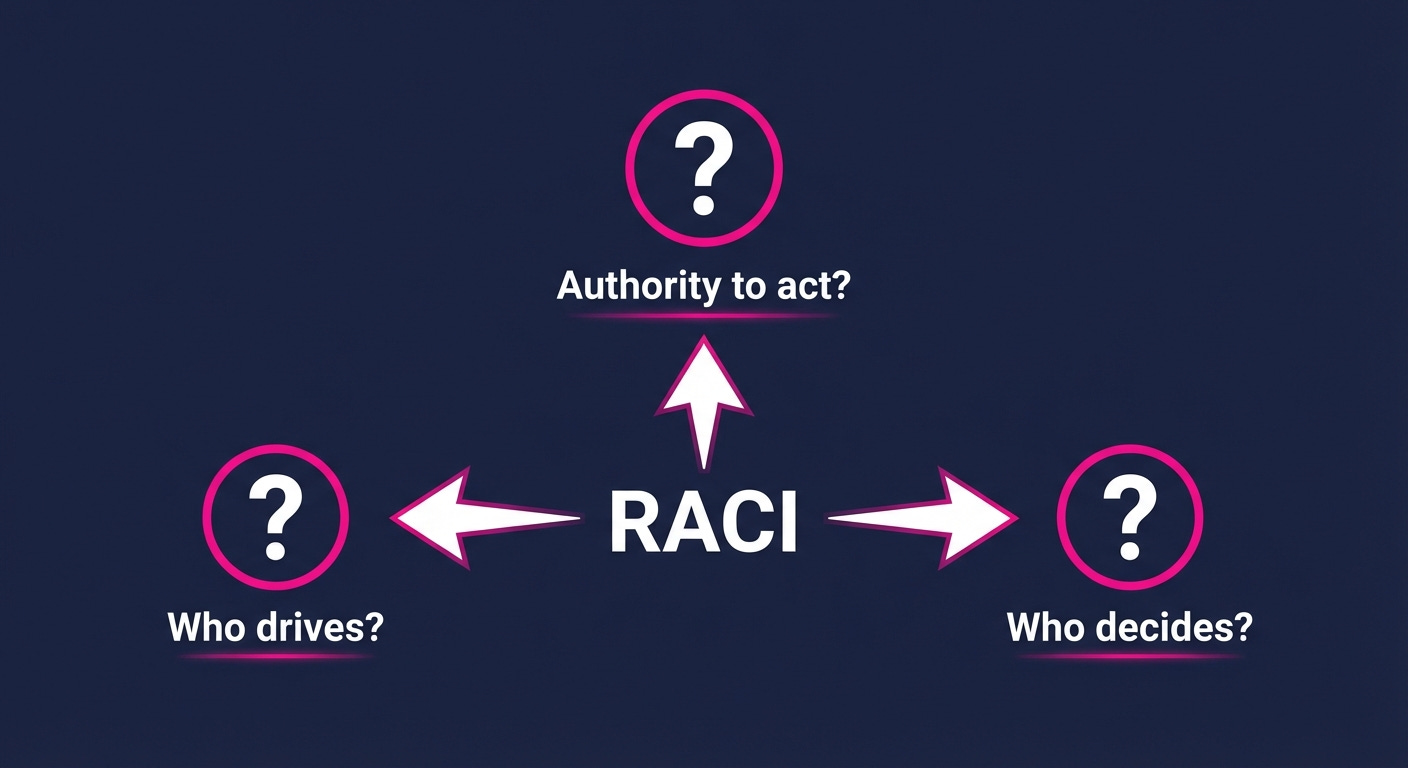

What RACI Gets Wrong

RACI emerged in the 1950s from management consulting. It was designed for internal projects with clear hierarchies: one organisation, one chain of command, one boss who could hold people accountable.

It defines four roles:

Responsible – who does the work

Accountable – who signs off (and supposedly “owns” the outcome)

Consulted – who gives input before decisions are made

Informed – who needs to know after decisions are made

This works nicely when:

One team delivers to one manager

Authority flows through a single hierarchy

The Accountable person has direct control over the Responsible person

Decisions stay within one organisation

It falls apart when:

Multiple vendors share delivery responsibilities

Authority is distributed across organisations

The Accountable person cannot direct the Responsible parties

Decisions require alignment across competing interests

In other words: it falls apart in transformation programmes.

RACI is not failing because people are incompetent. It is failing because it quietly assumes conditions that no longer exist.

It assumes a single organisation context, where authority and accountability sit within the same boundary.

It assumes line management authority, where the Accountable role can direct the Responsible role.

It assumes decisions are internal, not negotiated across contracts, vendors, and steering forums.

Digital transformation programmes violate all three assumptions by design.

The Three Gaps That Kill Transformation Governance

When you apply RACI to multi-partner programmes, three critical gaps emerge.

Gap 1: No Driver

Who ensures work moves forward?

Who engages stakeholders, schedules workshops, chases decisions, and removes blockers?

In RACI, the Accountable person is supposed to “own” this. But in transformation programmes, the Accountable person is often a senior sponsor, someone with ten other priorities who cannot drive work day-to-day.

The Responsible party does the work. But they are often a vendor who cannot force decisions from the client side. They cannot schedule workshops without client availability. They cannot resolve design disputes between client stakeholders. They cannot approve scope changes.

So work stalls. The vendor waits for the client. The client waits for the vendor. Everyone points at the RACI chart and says: “I did my part.”

In transformation programmes, “Driver” is not an optional governance enhancement.

It is a structural requirement.

If a deliverable, decision, or workstream does not have exactly one named Driver with the mandate and bandwidth to push it forward, it will stall. Not sometimes. Predictably.

Gap 2: No Decision Authority

RACI assumes Accountable = Approver = Decider.

In complex programmes, these are often different people.

Or committees.

Or informal consensus that never quite forms.

The result: decisions bounce between forums. They wait weeks for the next Steering Committee. They die in endless alignment meetings where everyone is consulted but no one is empowered to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

I have seen programmes where “Accountable” meant “will be blamed if this fails” rather than “has the authority to make this succeed.”

That is not governance. That is a setup for finger-pointing.

Gap 3: Accountability Without Authority

Someone is marked “Accountable” but cannot actually influence the work.

Architects labelled Accountable for solution designs they cannot enforce.

Architects are often treated as Accountable because they “own the design”.

But owning design quality is not the same as owning delivery outcomes.

Architects can be accountable for architectural coherence, technical integrity, and adherence to principles. They should never be accountable for delivery speed, vendor performance, or business adoption unless they control the levers that make those things happen.

Client managers Accountable for vendor deliverables they cannot control.

Programme directors Accountable for benefits that depend on business changes they have no authority to mandate.

This is pressure without power. It creates resentment, not results.

What Happens When No One Drives

These gaps create predictable failure modes. You will recognise them.

Failure Mode 1: Decision Paralysis

Everything escalates.

Design decisions that should take a day wait for the next Design Authority. Design Authority decisions wait for Steering Committee. Steering Committee defers to “offline alignment”.

A Fortune 500 manufacturing firm learned this the hard way during their global ERP rollout. They assigned regional business units as “Consulted” for global process templates.

The regions interpreted “Consulted” as “Consent Required”.

43 Regions flooded the programme with over 2,000 change requests to localise the processes. The system integrator ground to a halt, waiting for the Programme Director to resolve the conflicts. The Programme Director lacked the political power to overrule regional VPs.

The programme paused for six months. Five million dollars burned in “standby army” costs – consultants and contractors waiting for decisions that never actually came.

The RACI was perfect on paper. Everyone had their letter.

And the programme nearly died.

Failure Mode 2: The Blame Game

RACI becomes a legal document for post-mortems rather than a collaboration tool.

People hide behind their letter.

“That is not my R”.

“I was only Consulted, not Accountable”.

“The RACI says the vendor is Responsible, so this is their problem”.

I have watched vendors and clients spend more energy and time defending their RACI assignments than solving actual problems.

The framework designed to create clarity becomes a weapon for avoiding responsibility.

Failure Mode 3: The Integration Gap

In multi-vendor programmes, each vendor is Responsible for their piece. No one is Responsible for making the pieces fit together.

Vendor A delivers their scope.

Vendor B delivers their scope.

Neither works with the other because no one drove the integration. Each vendor points at the RACI: “We delivered what we were Responsible for, and what’s in our statement of work (SoW)”.

The client, marked Accountable for overall success, is left holding the pieces.

Failure Mode 4: The Anti-Agile Effect

Practitioners working in agile transformations often find RACI causes friction at the team level.

RACI focuses on individual accountability: “I did my job”.

Agile focuses on team accountability: “We delivered the value”.

When you overlay RACI onto agile teams, people revert to “ticket passing” behaviour. They complete their assigned task and throw it over the wall. The agile, collaborative, outcome-focused mindset breaks down.

This does not mean governance is unnecessary. It means RACI is the wrong framework for how modern programmes actually work.

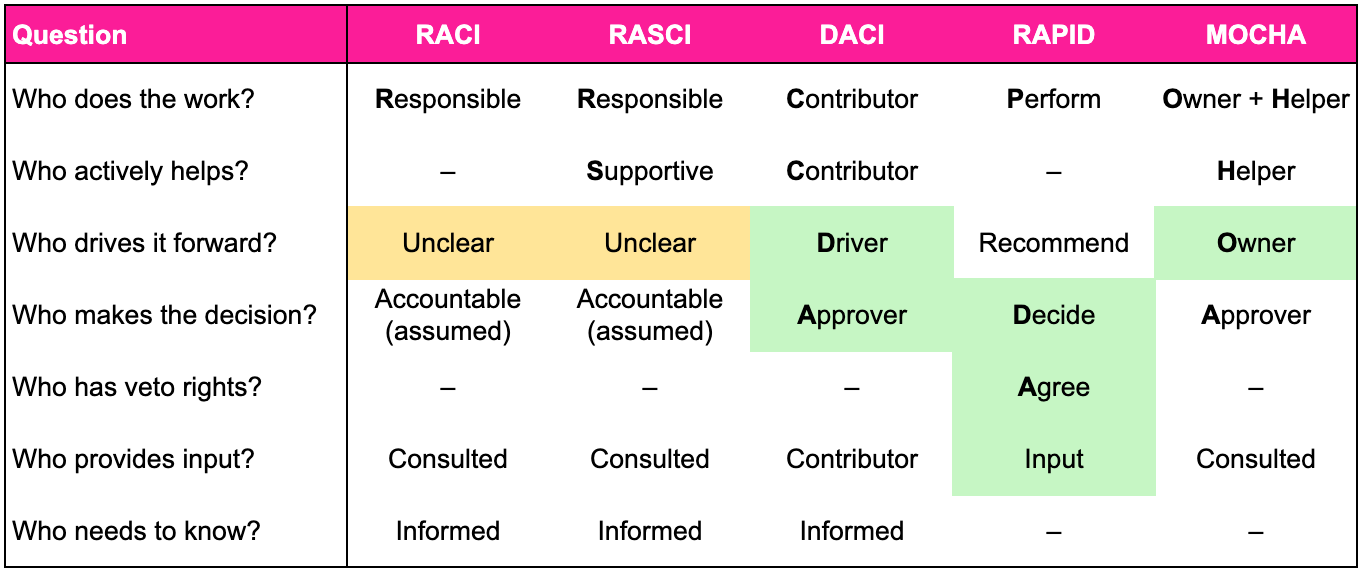

The Five Governance Frameworks: A Complete Review

RACI is not the only option. Four other governance frameworks exist, each designed to solve different problems.

Before choosing a governance framework for your transformation, you need to understand what each one does, and what it does not do.

Framework 1: RACI

Stands for: Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed

Origin: 1950s management consulting, designed for internal projects with clear hierarchies

What it defines:

Responsible: Who does the work

Accountable: Who owns the outcome and signs off (rule: only one A per task)

Consulted: Who provides input before the work is done (two-way communication)

Informed: Who is told after decisions are made (one-way communication)

What gap it fills: Basic task clarity, i.e. who does what

When to use it:

Single-organisation projects with clear reporting lines

Tasks where the Accountable person has direct authority over the Responsible person

Simple approval workflows

When NOT to use it:

Multi-partner programmes with shared accountability

Complex decisions requiring explicit decision rights

Situations where “Accountable” lacks authority over “Responsible”

The core weakness for transformations: RACI does not define who drives work forward or who makes decisions. It assumes the Accountable person does both. In multi-partner programmes, they usually cannot.

One-line summary: RACI tells you who does and who approves but not who drives or who decides.

Framework 2: RASCI

Stands for: Responsible, Accountable, Supportive, Consulted, Informed

Origin: Variant of RACI, adds a Support role for complex delivery

What it defines:

Responsible: Who does the work

Accountable: Who owns the outcome

Support: Who actively helps the Responsible party (hands-on assistance, not just advice)

Consulted: Who provides input

Informed: Who is told after decisions are made (one-way communication)

What gap it fills: Clarifies who is hands-on helping versus who is just advisory

When to use it:

Multi-party delivery where teams actively support each other

Situations where “Consulted” is too passive so you need people rolling up their sleeves

Vendor-client relationships where the client provides active support (data, access, decisions)

When NOT to use it:

When you need decision clarity (RASCI still has no explicit Decider)

When you need a Driver role (RASCI still assumes Accountable drives)

Why it is not enough for transformations: RASCI improves on RACI by distinguishing active support from passive consultation. But it still has the same weakness for transformation scale: no explicit Driver, no explicit Decider. Adding the Support role helps with execution clarity but does not solve the governance gaps.

One-line summary: RASCI clarifies who helps but still does not clarify who drives or decides.

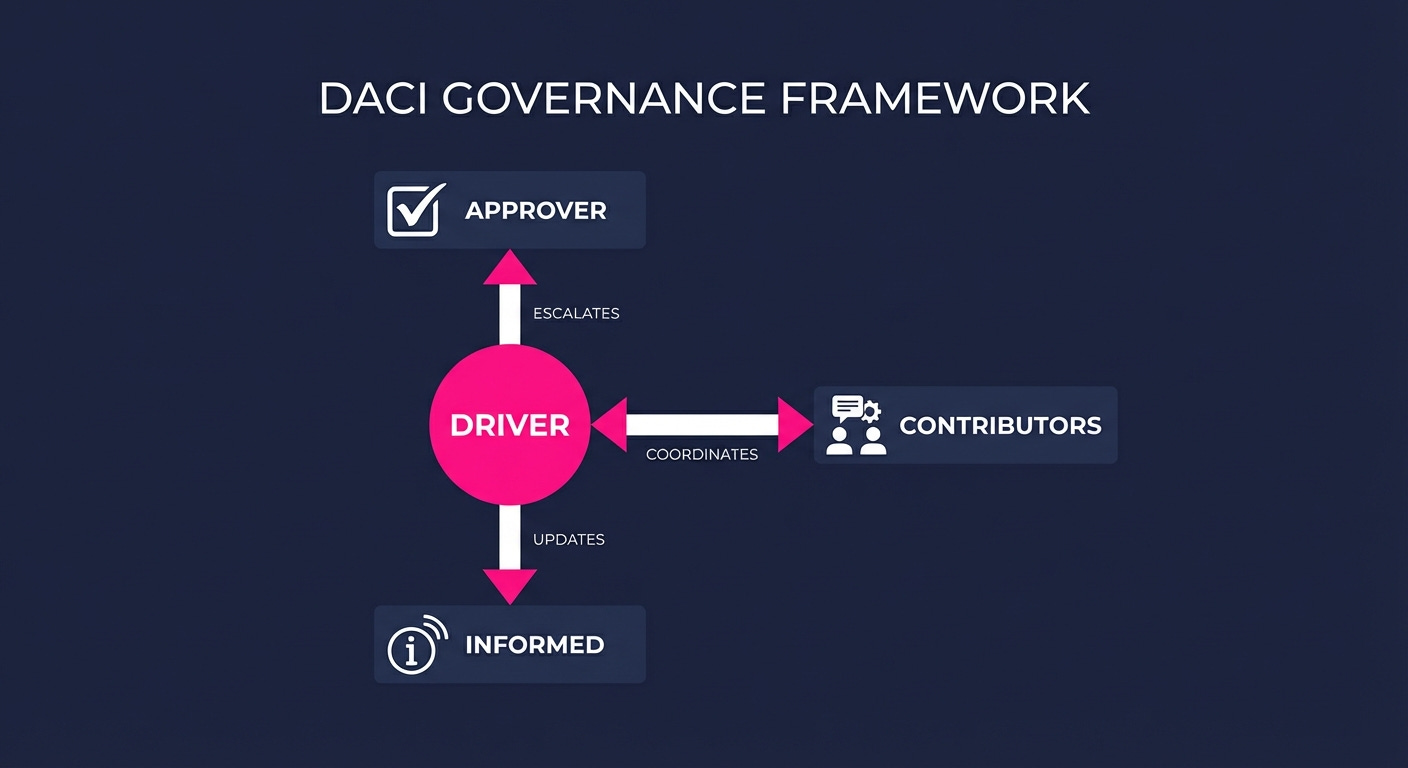

Framework 3: DACI

Stands for: Driver, Approver, Contributor, Informed

Origin: 1980s, developed for environments where decision-making clarity was critical

What it defines:

Driver: Who drives the work forward: coordinates inputs, schedules decisions, chases blockers, ensures progress. Does not do all the work but makes sure it happens.

Approver: Who makes the final call. One person with decision authority. Their ‘yes’ means go; their ‘no’ means stop.

Contributor: Who provides input and does parts of the work. Combines RACI’s Responsible and Consulted.

Informed: Who needs to know the outcome.

What gap it fills: Explicitly separates driving from approving. Names who keeps things moving, distinct from who makes the call.

When to use it:

Multi-partner programmes where no single party controls all the pieces

Workstreams and deliverables that require coordination across teams

Any situation where work stalls waiting for someone to “drive”

When NOT to use it:

Simple tasks where driving and approving are naturally the same person

High-stakes decisions requiring explicit veto rights (use RAPID instead)

Why it works for transformations: DACI directly addresses the Driver gap. The Driver is explicitly named and accountable for progress. Not just for doing work, but for making sure work gets done. This prevents the “everyone has a letter, no one is driving” problem.

One-line summary: DACI names who drives and who decides, the two things RACI leaves ambiguous.

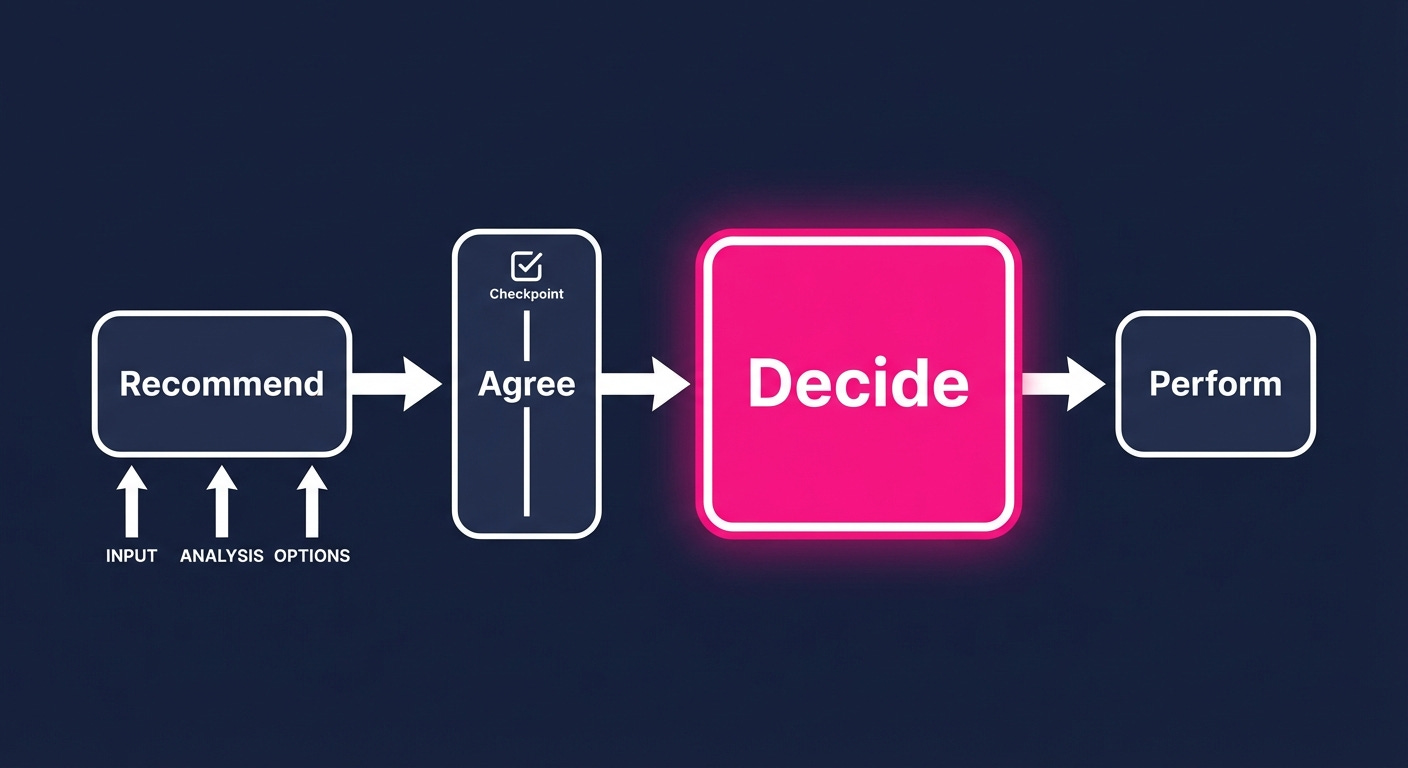

Framework 4: RAPID

Stands for: Recommend, Agree, Perform, Input, Decide

Origin: Bain & Company, early 2000s, designed for complex multi-stakeholder decisions

What it defines:

Recommend: Who develops the recommendation: gathers input, analyses options, proposes a course of action

Agree: Who must agree before proceeding – a formal veto right, used for compliance, legal, or technical feasibility

Perform: Who executes once the decision is made

Input: Who provides information and perspective influences but does not decide or veto

Decide: The single person who makes the final call. One person. Not a committee.

What gap it fills: Explicitly names the Decider and distinguishes input (no veto) from agreement (veto). Prevents decisions from dying in consensus-seeking.

When to use it:

Steering Committee or Design Authority decisions with multiple senior stakeholders

High-stakes decisions where multiple parties have legitimate interests

Situations where “Consulted” keeps being interpreted as “Consent Required”

Go/No-Go gates, major scope changes, strategic trade-offs

When NOT to use it:

Day-to-day workstream execution (too heavyweight)

Simple decisions where one person naturally owns the outcome

Why it works for transformations: RAPID solves decision paralysis by forcing clarity on who decides. The Decide role is singular. Input providers can influence but cannot block. The Agree role is reserved for veto requirements, not political comfort.

One-line summary: RAPID ensures one person decides and everyone else knows their role is input, not veto.

Framework 5: MOCHA

Stands for: Manager, Owner, Consulted, Helper, Approver

Origin: Nonprofit and social sector, developed by The Management Center for mission-driven organisations

What it defines:

Manager: Who supports the Owner and holds them accountable, provides coaching, removes blockers, ensures the Owner succeeds

Owner: Who owns the work, i.e. the single point of accountability for driving it forward

Consulted: Who provides input

Helper: Who actively assists the Owner (similar to RASCI’s Support)

Approver: Who signs off on the final output

What gap it fills: Separates ownership from management. Clarifies that the Owner drives while the Manager supports and holds accountable.

When to use it:

Programme leadership structure where sponsor and programme lead are different people

Situations where senior leaders need to support without micromanaging

Organisations that value coaching and development alongside delivery

When NOT to use it:

Corporate IT environments unfamiliar with the framework (requires explanation)

Decision-heavy governance where RAPID’s explicit Decider is more useful

Organisations that equate “Manager” with “Boss”

Why it may not be the best choice for transformations: MOCHA is excellent for clarifying leadership dynamics – who owns versus who supports. But it is less known in corporate IT and consulting circles. Introducing MOCHA requires education that DACI does not. For pure governance clarity, DACI achieves the same Driver/Approver separation with less friction.

One-line summary: MOCHA clarifies who owns and who supports, valuable for leadership, but less known in enterprise transformation.

The Framework Comparison: Which One Fits Transformations?

Key observations:

RACI and RASCI leave the Driver role undefined. They assume the Accountable person drives. In multi-partner programmes, this assumption fails.

DACI explicitly names the Driver. This is the core fix for transformation execution.

RAPID explicitly names the Decider and separates Input from Agree. This is the fix for decision governance.

MOCHA has an Owner role similar to DACI’s Driver, but is less known in enterprise contexts and requires more education to adopt.

Why DACI Wins for Transformation Execution

For day-to-day programme execution across workstreams, deliverables, cross-functional coordination, DACI is the right governance framework.

Here is why:

1. It names the Driver explicitly.

No more assuming the Accountable person will drive. The Driver role is defined, assigned, and accountable for progress. They coordinate, chase, escalate, and unblock. They do not do all the work but they make sure it happens.

2. It separates driving from approving.

The Driver keeps things moving. The Approver makes the call. These are often different people with different availability and authority. Making that explicit prevents confusion.

3. It is simple enough to adopt.

Four roles. Clear definitions. No extensive training required. Teams can start using DACI in days, not weeks.

4. It works for multi-partner delivery.

When you have vendors, clients, and third parties sharing responsibilities, DACI forces clarity on who is driving coordination, not just who is doing their piece.

DACI in Practice: The Multi-Vendor Success

A financial services organisation used DACI for a multi-vendor ERP- and data-enabled transformation programme. They explicitly assigned the lead system integrator as the Driver for the integrated cutover plan.

This meant the SI had to coordinate the ERP vendor, security vendor, the data vendor, and the client infrastructure team (all Contributors). They could not say “the data vendor is late” and shrug. As the Driver, it was their contractual obligation to chase the data vendor and escalate to the Client Approver only if blocked.

The result: no integration gap. No finger-pointing between vendors. One party was clearly responsible for making sure all the pieces came together. Not because they did all the work but because they drove it.

When to Add RAPID: Steering Committee and Design Authority Decisions

DACI handles execution. But some decisions are bigger. They involve multiple senior stakeholders, competing interests, and political complexity.

For Steering Committee and Design Authority decisions: major scope changes, design trade-offs, localisations, go/no-go gates – consider RAPID.

The power of RAPID is the explicit Decider. One person. Not a committee. Not consensus.

RAPID in Practice: Clearing the Backlog

Remember the ERP programme that burned five million dollars waiting for regional alignment?

They reset using RAPID.

Regional VPs were moved from “Consulted” (which they interpreted as veto power) to “Input” (perspectives welcomed, no veto).

A Global Process Owner was given the Decide role.

The System Integrator was assigned Recommend.

The backlog of 2,000+ change requests was cleared in six weeks. Not because the regions stopped caring. Because the right to veto was explicitly removed. The Decider could hear input and make the call.

This is what good governance does. It does not eliminate disagreement. It ensures disagreement does not paralyse progress.

When Governance Blurs: The ASX Lesson

The Australian Securities Exchange attempted to replace its CHESS clearing system with a blockchain solution. The project failed after years of delay and massive cost overruns.

Post-mortems revealed a governance structure where ASX tried to act as both the Platform Owner and the Systems Integrator despite lacking internal software depth.

The lines between “Client” and “Vendor” blurred. There was no clear architecture veto to stop scope creep. The codebase inflated from 300,000 to 1.3 million lines.

In RAPID terms: there was no Agree function to say “this is not technically feasible.” The desire for features (Input) was never separated from the feasibility of execution (Perform/Decide).

The lesson: governance frameworks must match reality. If you do not have the capability to act as the integrator, do not govern as if you do. And if decisions require technical feasibility checks, make that an explicit Agree gate, not an assumption.

A quick clarification on frameworks

Governance frameworks are not mutually exclusive. They operate at different layers.

DACI governs execution and coordination.

RAPID governs decision authority.

Agile roles govern team delivery.

The Recommendation: What to Implement

If you are a transformation leader deciding on governance, here is the practical guidance:

Replace RACI with DACI for programme execution.

For every major workstream and deliverable, name:

A Driver who ensures work moves forward

An Approver who makes the final call

Contributors who do the work and provide input

Informed parties who need visibility

Use RAPID for steering committee and cross-functional design decisions.

For major programme decisions (scope changes, design trade-offs, go/no-go gates), name:

A Recommender who develops the proposal (typically your lead implementation partner)

A Decider who makes the call (one person, not a committee)

Input providers who inform but do not veto

Agree roles only where genuine veto is required (legal, compliance, technical feasibility)

Why not RASCI? It adds Support but still lacks a Driver. The core governance gap remains.

Why not MOCHA? It has an Owner role that functions like a Driver, but is less known in enterprise contexts. DACI achieves the same outcome with less friction.

The Mindset Shift

RACI asks: “Who is accountable if this fails?”

DACI asks: “Who is driving this to success?”

That is not wordplay. It is a fundamentally different positioning, from blame assignment to progress ownership.

Questions to Ask (Without Getting Yourself Burned)

If you suspect your programme has a governance gap, here are questions you can raise without sounding like a cynic.

To surface the “Driver” gap:

“Who is responsible for making sure this moves forward, not just doing the work, but ensuring decisions get made?”

“If this stalls waiting for input, who chases it?”

“I want to make sure I understand who is driving this workstream. Can we name that person explicitly?”

To surface the “Decision” gap:

“Who will make the call if we disagree?”

“Is the Accountable person also the decision-maker or do they need to consult others first?”

“For this decision, who has the authority to say yes?”

To propose a fix without confrontation:

“It might help to name a Driver for this workstream, someone who keeps it moving day-to-day, separate from the Approver.”

“Can we clarify who the single Decider is for this? I want to make sure we do not end up in circular alignment.”

These questions position you as diligent, not difficult. You are trying to make the programme succeed and you need clarity to do your job.

A Note on Agile Programmes

If your transformation uses SAFe or another agile framework, you may find RACI causes friction at the team level.

This is expected.

RACI focuses on individual accountability: “I did my job.”

Agile focuses on team accountability: “We delivered the value.”

Successful agile transformations often abandon RACI at the squad level entirely.

Teams rely on Scrum roles (Product Owner, Scrum Master, Team) for day-to-day work.

They retain RAPID only for portfolio-level decisions that span multiple teams or trains, the decisions that still require explicit authority.

The principle holds: use the governance framework that matches the work. DACI for cross-cutting coordination. RAPID for strategic decisions. Agile roles for team-level delivery.

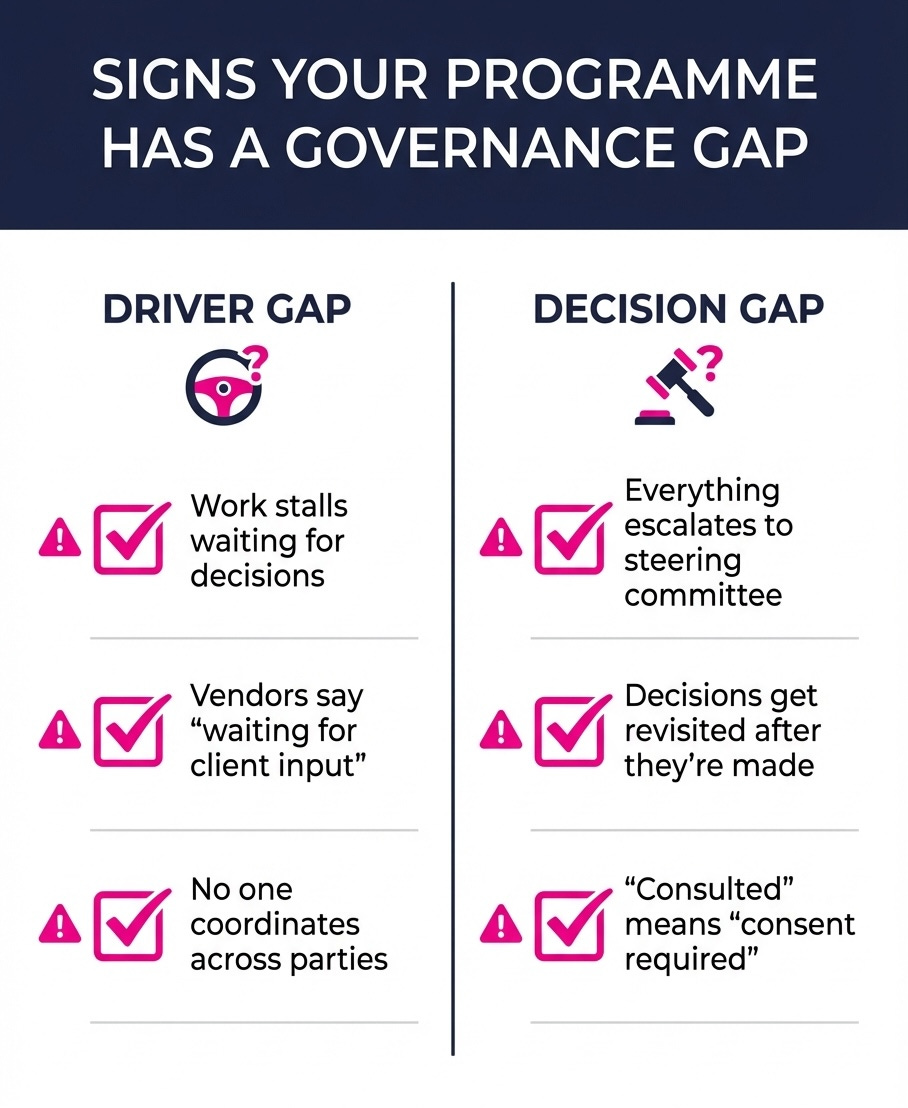

The Governance Diagnostic

Signs your programme has a “Driver” gap:

Work stalls waiting for someone to chase decisions

Responsible parties say “we cannot move without client input”

Accountable parties say “I am waiting for the vendor to deliver”

No one is explicitly named to coordinate across parties

Signs your programme has a “Decision” gap:

Everything escalates to Steering Committee (and sometime beyond)

Decisions get revisited after they are made

Multiple people believe they have veto power

“Consulted” is interpreted as “Consent Required”

The fix:

Replace RACI with DACI for deliverables and workstreams

Optionally, use RAPID for major cross-functional and execution decisions

Name a single Driver and a single Decider for everything that matters

Make sure the Driver has the mandate and the bandwidth to actually drive

The Bottom Line

RACI tells you who does the work. It does not tell you who drives it.

In multi-partner transformation programmes, that gap is fatal.

Work stalls.

Decisions bounce.

Accountability becomes blame.

Five governance frameworks exist. For transformation execution, DACI wins: it explicitly names the Driver and the Approver. For steering committee decisions, add RAPID: it explicitly names the Decider and separates input from veto.

The next time someone pulls up a RACI chart and asks “who is Accountable?”, try a different question:

“Who is driving all of this?”

If the answer is not immediate and clear, you have found your governance gap.

A simple rule for sponsors and programme leaders:

If progress depends on goodwill, informal escalation, or heroic individuals, your governance is already broken.

Good governance does not rely on people stepping up. It makes responsibility unavoidable.